Exhibitors react to the industry’s first trade show since the Covid-19 pandemic struck in March of 2020.

By Timothy S. Donahue

The vaping industry has a lot of trade shows and conferences every year. So, when the Covid-19 pandemic struck in March 2020, it was a big change. Gone were face-to-face meetings and the networking opportunities the events offer to business owners. Many businesses saw sales slump and profits nosedive. Coupled with other regulatory requirements, the pandemic caused many businesses to close.

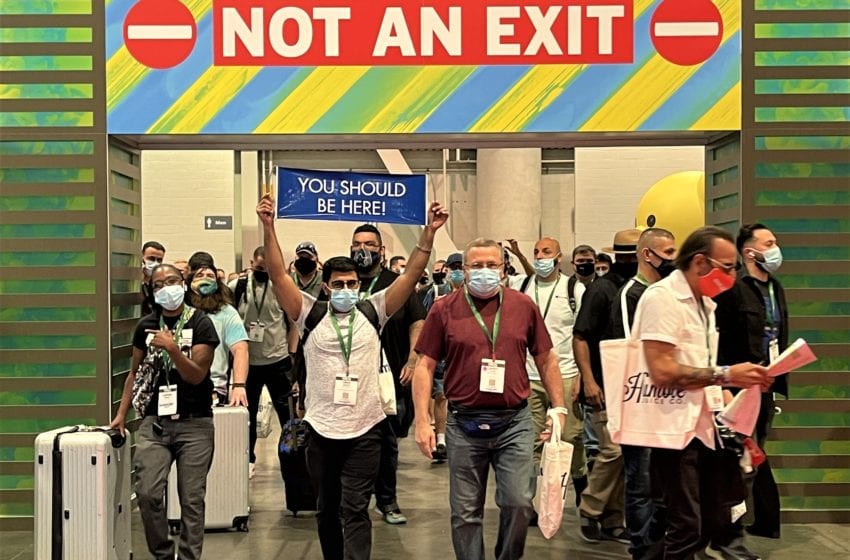

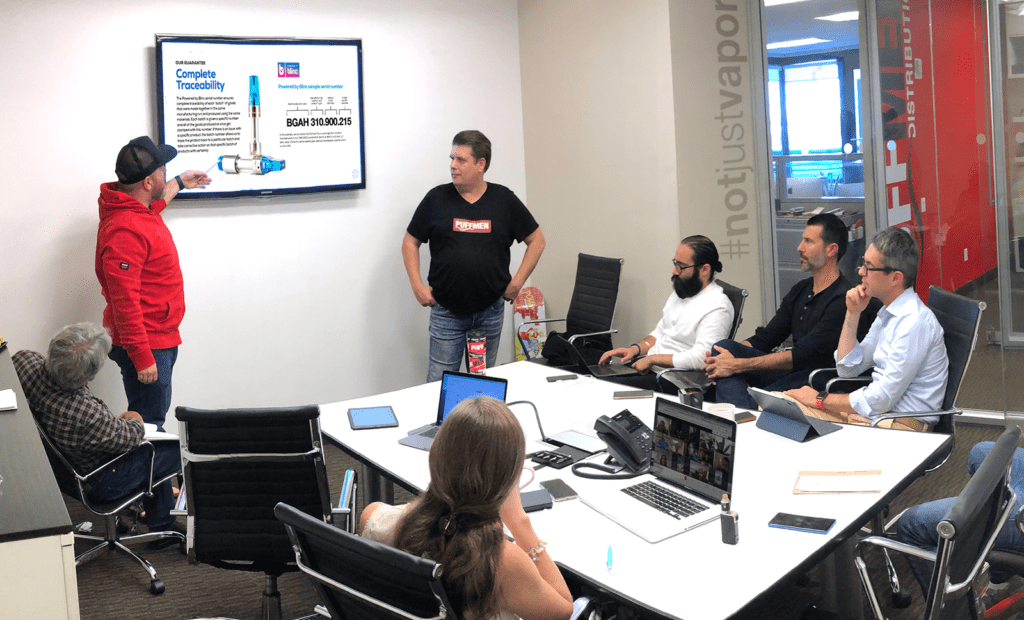

That’s what made this year’s Tobacco Plus Expo (TPE) trade show so special. After being postponed nearly four months, many retailers said they had surpassed their sales goals for the entire show on the first day. TPE attendees said it was a good feeling being able to fist bump clients and talk about the industry in person instead of through a Zoom conference. The TPE felt like the beginning of a much-needed return to normal.

Held May 12–14, an estimated 2,500–3,000 people visited the TPE on the opening day of the three-day event. According to security staff, approximately 4,000–5,000 attended overall. Every morning, several hundred attendees waited at the entrance to see the more 350 exhibitors. The show was moved to May from its typical January date due to the pandemic and was also the first major trade show to be held at the Las Vegas Convention Center (LVCC) since it closed in March of 2020.

Even professional poker player Dan Bilzerian, owner of the Ignite cannabis brand, made an appearance. “Honestly, I’m excited to be back,” Bilzerian said. “This industry is really set to take off again.” When asked about Ignite sales at the show during the second day of the event, Bilzerian said the numbers looked good. “We hit our sales target for the show on our first day,” he said. “We’ve had an excellent response.”

Many exhibitors said that the show had exceeded expectations. Rich Zagari, a sales representative for Bantam Vape, said they were unsure of what the show would be like considering it was the first industry trade show in over a year. “We didn’t know what the response was going to be, but there’s a lot of people here,” he said during the second day of the show. “Yesterday was great and today’s already shaping up to be even better. When you’re seeing customers come up to the booth, having conversations and placing orders, it makes a difference. It’s good to be back doing business face-to-face.”Zachary Kestenbaum, VP of sales for The Beard brand, said that while he was hoping for a bit more foot traffic this year, for his company the TPE was more about getting facetime with distributors, vape shops and other industry players. “I enjoy face-to-face sales more than phone sales, anything of that nature,” he said. “I think it’s much better to conduct business outright. In that regard, the show has been a great success.”

Some exhibitors initially questioned whether the show would be able to bring in foot traffic at all. Andy Lucas, director of sales for Ripe Vapes, said with the influx of restrictions, such as the premarket tobacco product application (PMTA) requirements for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the recent placement of electronic nicotine-delivery systems (ENDS) under the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act, alongside the issues brought about by Covid-19, he was a little hesitant about exhibiting.

“Actually, it’s been pretty good. It’s been more like a traditional show, especially for a big show like this. You got all these organizations with tobacco and the hemp industry, the e-liquid industry; it has really lived up to the hype surrounding its opening,” said Lucas.

Jakob Gutierrez, product specialist for JustCBD, said he was happy to be back in Las Vegas. The attendees were also ready to spend money. While he had hoped for even more buyers to visit the TPE, JustCBD had received more orders by Day 2 of TPE than the company had gotten at the last couple of shows it attended, according to Gutierrez. “People keep stopping by and loving our products,” he said. “People are absorbing it, taking it and just asking us for more. We keep providing high-quality products, and our customers keep coming back.”

There was a noticeable reduction in the number of nicotine vaping companies showing on the floor. The impact of PMTA and PACT Act regulation was evident. There were only an estimated 16–18 e-liquid vendors, including Coastal Clouds, BLVK E-liquid and Fresh Farms. There were an estimated five to seven hardware manufacturers, including Mi-One Brands, Myle, NJoy and Inspire, and most of them produced their own brands.

There was also a noticeable reduction in international participants, said Tony Riva, CEO of TD Distribution Co., the parent to the Hi-Drip e-liquid brand, which was also exhibiting. Normally, there are at least 20–30 exhibitors from China alone; this year, there were only a few Chinese brands present, and the booths were manned mostly by U.S.-based personnel.

“The international community that is normally present at this show just isn’t here this year. That’s obviously due to the Covid restrictions and complications of international travel,” he said. “That’s having an impact on sales, I think. But business is good. We are just trying to navigate the changing regulatory environment and new policies that have been put in place.”

Regulatory concern

Before the show, exhibitors were concerned about what impact the PACT Act would have on show sales. The rule requires a manufacturer to gather data from customers to file the mandatory monthly reports with native, state and local governments disclosing the identity, address and product received for all customers as well as remit any excise taxes owed.

“As a best practice, it’s our priority to collect licensing information upfront from any new customer and we were glad potential buyers came to the show prepared,” said Zagari. “They had copies of these documents on hand or emailed them right away.”While many companies have already stopped using the United States Postal Service (USPS) because the PACT Act prevents the USPS from mailing ENDS products to customers, the rules have not yet taken effect. At the time of writing, the USPS had yet to publish the finalized rule. Lucas said Ripe Vapes had a large following for online sales. However, Ripe Vapes has ended all direct-to-consumer sales because of the PACT Act and now only conducts B2B sales in the U.S. “It was a difficult decision,” he said. “In the end, it was the right one to make.”

Zagari said Bantam plans to ship through USPS until the final rules go into effect. “We are working to identify alternative shipping options, which will help us continue online consumer sales once the USPS final rule is published,” he said. “It’s our goal to ensure our customers always have access to our high-quality, flavor-filled e-liquids that are in compliance with all regulatory requirements.”The PACT Act’s definition of ENDS is so broad that it includes vape-able hemp cannabis products too. JustCBD only sells cannabis products and felt that they were “suckered in” to the ENDS definition, according to Gutierrez. The company has filed an exemption with the USPS, but that exemption will not be considered until after the final rule goes into effect. “It seems like we are jumping through a lot of hoops to sell a legal product that has nothing to do with nicotine or tobacco,” Gutierrez said.

Beyond the PACT Act, TPE exhibitors and attendees remain concerned about the PMTA process and the full impact of FDA regulation on the vaping industry. Numerous companies, including major industry players like Dura Smoke, My Freedom Smokes, Logic and Vape Wild, have gone out of business, merged with other companies or ended all online sales.

Kestenbaum said that as the market condenses and regulation pushes players from the market, naturally sales to the companies that remain would increase. The recent release of the list of manufacturers that have submitted PMTAs has also served a guidance for vape shop owners. Companies cannot now claim they have submitted a PMTA without having done so.

“So many companies were saying, ‘We’re going through PMTA. We’re doing it. We’re doing it,’ and they weren’t. I think we are starting to see many of those companies drop out of the industry, said Kestenbaum. “We’re trying to run everything by the book … I feel like we’ve gotten burned for doing that because there were a lot of companies that were not. The PACT Act, PMTAs, these aren’t all bad. Let’s clear out the lawless, let’s get a little bit more organized and allow the ones doing the right thing to continue.”

Lucas said Ripe Vapes submitted only one PMTA for its VCT flavored e-liquid. The company has a considerable international business, so its other popular flavors, such as Key Lime Cookie, are still available outside the U.S. “Our attorney said, ‘Look, your best chance … the way this is going to go, looking at it from a cost standpoint, take your No. 1 e-liquid and just roll with it,’” said Lucas. “Some of these guys are trying 10, 15 or 20 flavors. They may get it if they have enough money, and there’s a couple of guys in this industry that probably do have enough money.”

Another concern is that the FDA has been taking its time in reviewing PMTAs, according to Lucas. He doesn’t see a path for the regulatory agency to complete reviews on the more than 6 million PMTAs submitted by the 1-year deadline (Sept. 10, 2021).

“We find it kind of hard to believe they’re going to have this done by next year. That’s what my next question is: What happens? Do they give you an extension? I think the industry is going to force them to make some decisions because you’re putting us through this,” explains Lucas. “The submittal alone for us was huge. So, when you’re spending all this money, you want some results. … It’s going to be an interesting thing as that deadline approaches.”

Bantam Vape has received a filing letter for its submitted products, according to Zagari. He said that the company hopes to hear back from the FDA soon but is preparing for the likelihood that the agency will not complete all reviews come September. “We are working to better understand our options and in the meantime, we are continuing to monitor FDA communications and actions.”

TPE 2022 will be held Jan. 26–28, 2022, in Las Vegas.